FLGOFF Frederick John Inger 408583

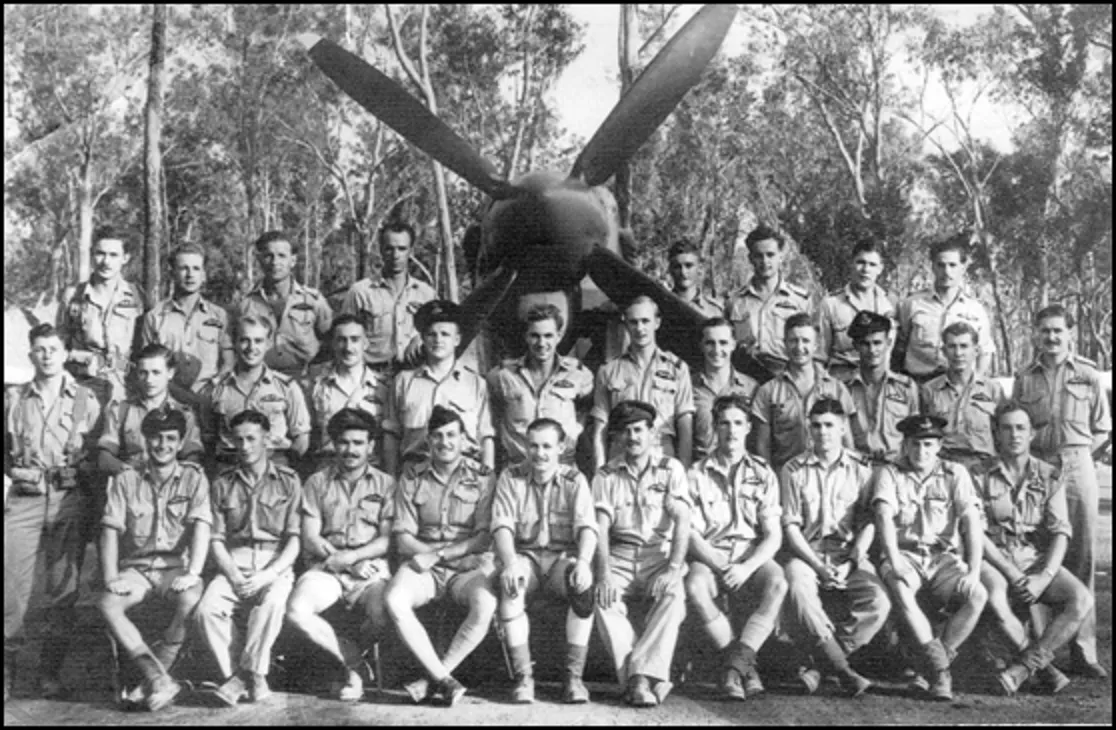

| Squadron/s | 457 SQN |

| Rank On Discharge/Death | Flying Officer (FLGOFF) |

| Nickname | Fred |

| Mustering / Specialisation | Pilot |

| Date of Birth | 03 Dec 1918 |

| Contributing Author/s | Vince Conant, 2013 The Spitfire Association |

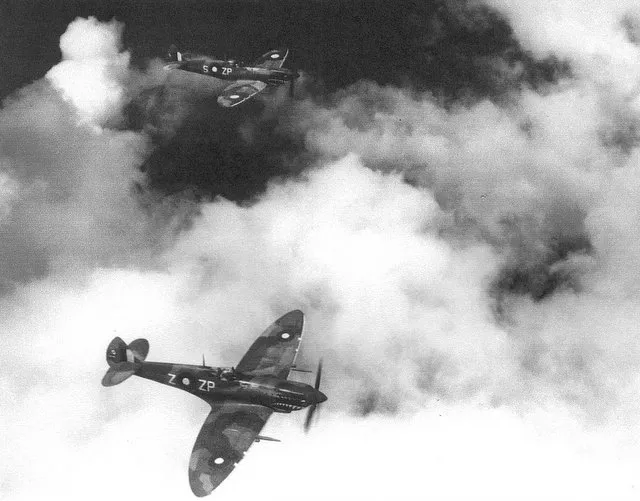

In 1945, the tide of the war in the South Pacific turned firmly in the Allies’ favour. Not included in the campaign for the recapture of the Philippines, Nos. 80 and 81 Wings RAAF were left behind on Morotai, a large island located in the Halmahera group of northern Moluccas, supporting the invasion of Borneo in May and June of that year. In June, the squadron was redeployed to Labuan Island off Borneo.

Because of the overall war situation and the distance to the Philippines, which remained outside of the operational radius of the Spitfires Mk. VIII that the Australians operated, there was no Japanese opposition in the air. In this situation the RAAF Spitfire squadrons were assigned to ground attack duties for “mopping up” of the remaining Japanese defences in the area. Over the jungle-covered and mountainous terrain of Borneo, these missions were difficult and hazardous. The jungle provided easy means of camouflaging any activity on the ground, so the pilots often had to fly at low level to spot any targets at all – most often barges or other vessels – and the risks of being shot down by ground fire were substantial.

In the first months of 1945, the two wings had lost fifteen aircraft and 11 pilots missing. For anyone who managed to bail out from their damages aircraft, the jungle was an inherently dangerous place offering slim chances of survival. All flying personnel was briefed on what to do, but few made it, especially if they had to jump far behind the enemy lines.

Here is the story of F/O Fred Inger, pilot of No. 457 “Grey Nurse” Squadron RAAF, who survived the parachute jump over Borneo from his aircraft on 11 July 1945.

In the afternoon of that day, the squadron was assigned just another armed reconnaissance mission to search for the remaining Japanese forces over British North Borneo. The squadron despatched four aircraft. Fred was flying a Spitfire Mk. VIII A58-633 as a wingman to the unit’s CO, Sqn/Ldr Bruce Watson.

The formation was approaching their target area in North Borneo when at 5:10 pm the engine of Fred’s Spitfire suddenly cut. Instinctively, he checked his fuel cocks, but these were in correct positions. He switched on the electric pump and oil, but with no results. A quick glance at the altimeter ensured him that he had to abandon the aircraft very soon; otherwise the altitude would be too low for the parachute jump. He called his number one, squadron CO shortly stating what he was going to do.

He glanced quickly around the landscape to assess his position. There was a clearing with huts nearby. In general, the villages were to be avoided; they could provide shelter to the Japanese soldiers, or locals which were hostile to British airmen. Considering this, Fred decided to keep his course and bail out over some heavily timbered country. He slid the canopy back and undid his harness. In the stress of the situation, he forgot to trim the aircraft nose down before climbing out of the cockpit. Now, struck by the slipstream, he found it very difficult to get out. He pushed himself up with all his strength and fell clear, very nearly being hit by the tail plane. He pulled the cord of his parachute and the canopy developed fully just a few seconds before he reached the ground. He saw himself falling directly towards a large tree. Pulling the side of the parachute sharply, he managed to steer clear of it. He cracked through smaller branches, striking a limb on the way. Then suddenly the parachute caught on the tree above him and he stopped abruptly. He didn’t stop completely. Under the weight of his body, the parachute pulled through and Inger continued to slide down. Finally, the canopy stuck on one of the lower limbs and he rested hanging a few feet above the ground. He could release his harness and jump to the ground. His stricken leg hurt upon the impact. Examining it he realised that he tore his flying suit and rendered his dinghy unserviceable. This was bad news as there were many water obstacles in the area, and getting to an open water presented his best chance of being picked up by Allied rescue aircraft.

When the first shock disappeared, Inger noticed the sound of firing. Panic struck at first when he thought that there was a party of Japanese nearby. Then he realised that his aircraft struck the ground somewhere nearby and the sound came from the ammunition exploding in the burning wreck.

The first thing to do now was trying to conceal the site of his landing from the Japanese which were likely to search for him. Inger buried his Mae West under the tree. Then he tried to remove the parachute, but couldn’t succeed, so he had to leave it as it was. He opened his E-3-J emergency kit and took out the matchbox-size compass. It was a small compass of mediocre quality and he couldn’t get a bearing; it seemed quite useless. Judging from the position of the sun, he set out roughly towards the East and made his way through the jungle, hoping to make his way to the coast.

He had to hack his way over jungle-bound ridges, cutting his way through the vegetation with a knife. He had to put on his flying gloves to protect his hands, but even so his progress was rather slow. While proceeding along a ravine, walking in water, he saw an imprint of a service boot. The Japanese seemed to be in the area.

Approximately one hour before dark, Inger reached the top of a hill. It was clear of timber but covered with a heavy growth of kunai grass. There he decided that his badly damaged dinghy was of no further use. He was just in the process of hiding it when he heard a measured noise as of someone walking. He hid quickly in the grass and remained still for endless minutes as the voices stopped nearby. Close to the sunset, the noises finally moved down the hill and died away.

Inger was now wary and started to be hungry. There was a lot of wild animals in the area – mouse deer, wild pigs, squirrels, monkeys and parrots. Hunting one of these with his pistol wouldn’t be very difficult, but after the evening’s incident Inger was concerned that a shot would give away his whereabouts and decided to endure without food.

He decided to spend the night at the clearing. He chose a spot at the centre of the patch and out grass until he had a three-foot pile to serve as a makeshift bed. He also tried to mend his flying suit and used some iodine off the escape gear, rubbing it over all the scratches on his body. Sleeping out in the wild, he had nothing to protect himself from the mosquitoes. He put on his flying gloves to protect the hands and made a mosquito net for his head with three small silk maps provided in the escape kit. This was not nearly enough to keep the invasive insects away, but at least offered some kind of protection. During the night he remained half-awaken brushing off mosquitoes that he felt on his face. It started raining. Then he dozed off. He woke up with a feeling of something else crawling across his face. Violently, he shook it off. It was a snake. A quick trip down to Suliman Lake and a welcome ride back to base in a RAAF Catalina and his day was done!

A58-633 HF.VIII MV129 Arrived in Australia on SS ???? 12/11/44. Rec 2AD ex UK 22/11/44. Allocated 9 RSU Reserve Pool 05/01/45. Rec 457Sqn RAAF 22/01/45. Lost on sortie 1710hrs 11/07/45 near Techilian Village in British North Borneo. Some 30 minutes after take-off and at 6500ft, the engine failed. F/O F J Inger Serv#408583, turns aircraft on a heading towards the coast in a hope to glide to the sea. Approximately some 12-15 miles from the coast, he was forced to bail out over some heavily timbered countryside. He stayed on site overnight and travelled the next day to Suliman Lake where he was picked up by a RAAF Catalina Flying Boat piloted by F/Lt W Mills DFC. SOC 22/07/45.