SGT Kenneth James McKenzie 23906

| Squadron/s | 457 SQN |

| Rank On Discharge/Death | Sergeant (SGT) |

| Nickname | Ollie |

| Mustering / Specialisation | Armourer |

| Date of Birth | 20 Sep 1906 |

| Date of Enlistment | 16 Dec 1940 |

| Contributing Author/s | Ian McKenzie, Bruce Read and Paul Carter The Spitfire Association 2011 Reviewed March 2014 |

Ollie McKenzie was born on the 20th of September, 1906 and enlisted at the age 0f 34 in the RAAF on the 16th of December 1940. He was promoted to Sergeant on the 1st of October 1943. He did his initial training at Amberley, Qld; his armour training at Point Cook, Vic and Tocumwal to become a Fitter-Armourer.

He served at Amberley, Point Cook, Westhampnett, Perranporth, Andreas (Isle of Man), Red Hill, Livingstone, Nhill, and Amberley at the end of the War.

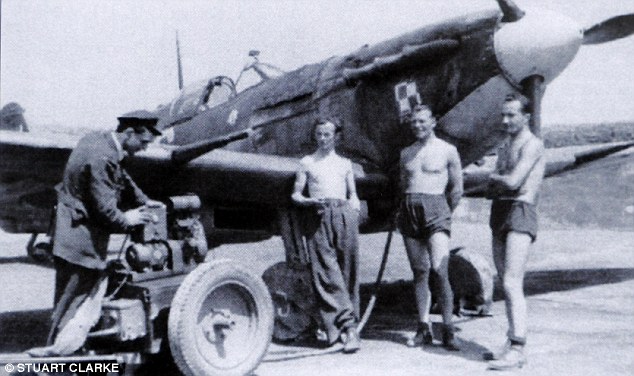

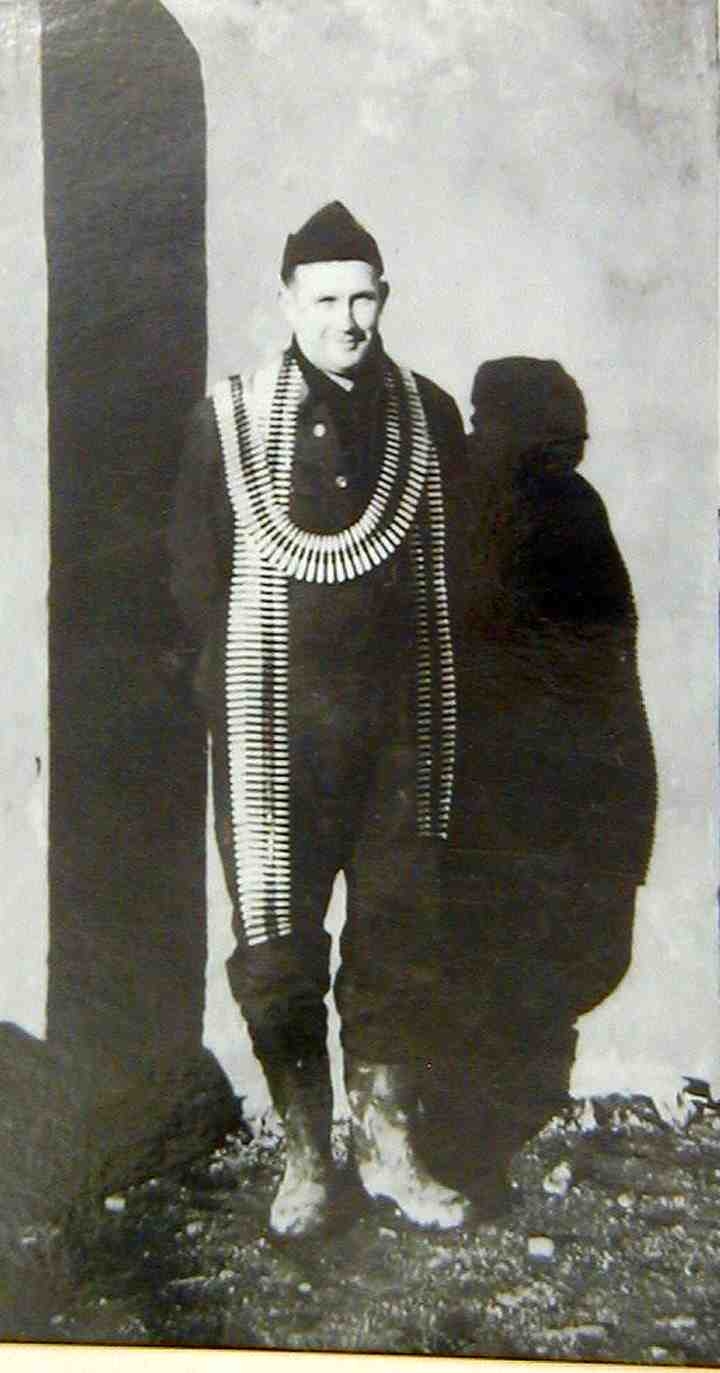

[Editor] Bruce Reid had a visit from Jim 'Ollie' McKenzie's son Ian in 2009. Ollie, a 457 Squadron Armourer older in years than most of us, died several years ago and Ian was keen to meet some of his father's WW11 mates to help him identify the airmen in several old snaps he trundled along. He also left copies of wartime letters his father had written to his brother for me to read and use if needs be. This photo of 'Ollie' McKenzie, was taken at the rear of 457 Squadron's armoury at Andreas on the I.O.M.

One was about a 1/6d per head levy that loony Williamtown C.O. S/L Paget tried to wring out of all the airmen about to depart for the U.K. In 1941, for items (jugs, cutlery, plates, camp ovens, mops and brooms, you name it for God's sake), that had gone missing from the airmen's mess. I think he was laughed off the paddock. I was there, but cannot remember this incident. I suspect some cookhouse wallah was flogging the stuff in Newcastle.

For the story on Jim we reproduce an article appearing in a newspaper from Ottawa, Canada (Monday).

A detachment of 1,000 Canadian, Australian and New Zealand and British airmen recently walked off a troop transport at a Canadian east coast port in protest against conditions for the Atlantic crossing it is revealed here. Veterans in a campaign in Crete were in a ship when the airmen boarded it and then disembarked. All but 200 or so returned on board after being urged to do so by officers. The others appeared before a court of enquiry.

A Canadian sergeant-pilot said, "The men were jammed in like sardines, 400 being supposed to sleep in one room with only ten wash basins. The sleeping equipment was dirty". Mr Power, the Canadian Air Minister, has stated that there need be no fear of a repetition of the unfortunate incident which the tides of war accidents of weather and errors of human judgment combined to provoke.

He admitted that there had been grounds for complaint but disagreed with the airmen's method of expressing disapproval. The ship was all the Admiralty had available he said. The conduct of the men apart from their firm refusal to sail as exemplary; this was taken into account when the men were disciplined by a reduction of pay: They all sailed later in another ship.

Ollie's son Ian said, "Jim was 34 years old and married with a two year old son (me) when he applied to join the RAAF in 1940. That makes me 71 years old now.

A past President of the Spitfire Association, Lysle Roberts, may have told you that I am writing the story of my father's war service from letters he wrote to my mother and his brother during those years. In fact, I have all the letters my parents exchanged. They make fascinating reading especially for me as I get a mention in nearly all of them. [2009]

When he wrote these letters he included information he thought his wife and brother would find interesting. He also had the censor in mind. Therefore, much of the work he did and the thoughts he had were not included. He did keep a detailed diary for every year of his service and he was meticulous in recording day to day details. I read these diaries when I was 17. Unfortunately, before he died in 1979 aged 73, he had buried them somewhere on our farm. Apparently, he got a bee in his bonnet and didn't want them to survive. What a loss! I can only write from the information I have and I know there are gaps and errors in dates, places and more than I care to think about.

I commenced this story during last year's wet season by cataloguing his letters and writing that part of the tale from his enlistment to his leaving the Isle of Man in March, 1942. When the wet season ended I had other things to do and I have only now resumed my writing. (It's too wet to do anything else just now.) I'm currently doing the Red Hill chapter and his last weeks in England. There's not much to write about the journey back to Australia because I have no letters about that. Then there's the time he spent at Livingstone. After that I'm a bit uncertain. I know he undertook a Fitter's course and re-mustered as a Fitter Armourer, but not, I think, with 457 Squadron. He ended his service at Amberley, from where he started, and resumed farming after his discharge.

Staff Officers responsible for the deployment of personnel now made the decision to post the 13 Australians to 66 Squadron at Perranporth in Cornwall for advanced training and to gain further experience.

The 13 left Westhampnett on the 17th of October, 1941 for what was expected to be a straight forward movement to Perranporth. So much so, that rations were not distributed for the journey. In the event, they were carried through to Penzance where, per favour of the Station master, they were able to over-night in a railway carriage. After scrounging a light breakfast - Jim had not received regular pay since leaving Australia- they entrained for Red Ruth and thence by tender to Perranporth. In all, the trip took 48 hours.

Jim was struck by the beauty of Perranporth, situated as it was next to a small bay. However, he soon discovered that all the seasons of the year could be experienced in one day. He was also impressed with all that Cornwall had to offer despite its weather. The culture, the history, the buildings, the ruins, the small paddocks with their stone fences, and the famous Cornish pasties, were all fascinating and enjoyable. The only wire fences Jim saw were along the permanent way. He reckoned that in the few weeks since arriving in England he'd seen more of the country than many Englishmen.

The hours of work on the aerodrome varied from day to day. Most duties involved maintaining the aircraft's armament, sighting and harmonising the guns, and doing daily inspections. Jim remained convinced that the RAF method of harmonising guns was not as good as the way he was taught at Point Cook.

Adverse weather conditions were also a consideration. Removing guns from an aircraft in freezing conditions was always a painful job, with frozen and stinging fingers to contend with. In strong windy conditions, men were required to sit on the tailplane while the guns were harmonised and tested. Outdoors work was virtually impossible when the wind reached gale-force strength, causing the men to seek warmth around the Armoury stove. As the Armourers had not been supplied with all the necessary tools of their trade, they had to forge the missing items in the workshop. The subsequent issue of Wellington boots was much appreciated by the Australians.

In mid-November, two Spitfires were involved in a ground collision causing moderate damage. Luckily, no one was injured. However, the job of removing the guns and ammunition from the damaged planes provided an unexpected opportunity to scrounge some scraps of aluminium and Perspex which were subsequently used to cast model Spitfires.

The billets on the Base were initially without lights and running water, necessitating a night-time walk of one mile to the canteen for letter writing. A kerosene tin on top of the billet's small coal-burning stove was used for washing clothes which were then hung over-night in the hut to dry. The same tin was used to brew tea. When coal was in short supply, as was usually the case, old car bodies found on the Base were stripped of their wooden components to fuel the stove. An old door was converted into a table to make the billet more liveable.

The airmen faced a one mile walk to their mess each morning and from there a two and a half mile ride to the armaments section.

Jim described one evening's meal as consisting of tinned herring, bread and butter with a little jam, and sweet tea. Another consisted of one thin slice of bread with butter, one thin slice of cheese, two thin slices of cake and two cups of sweet tea. Smelly, inedible fish cakes appeared on the menu from time to time. Jim was spending about 5/- a week at the NAFFI to appease his appetite.

Always the farmer, Jim was interested to learn the farm-gate values for local produce. For example, peaches brought 1/3 each, strawberries 3'6 lb., grapes 7/6 lb. Rump steak at the local butcher's sold for 1/6 lb. Sugar at the grocer's fetched 4d. a lb.

Jim was now becoming accustomed to air-raid warnings, although no bombs fell near Perranporth while he was there. To Jim's mind, the black-out curtains in the hut were fairly defective. Despite all efforts to correct this, the possibility of having the lights removed was always on the cards. Falmouth was a frequent target, and the flashes and explosions could be clearly seen and heard. Truro was thought to have had some near misses as well during this time.

Jim made excursions into Truro and Red Ruth when the opportunity arose. Truro, with a population of 13,000, boasted an impressive cathedral built along Gothic lines. Less impressive were the narrow streets and old dwellings.

Rumours seemed to be as much a part of RAF life as they were in Australia. Oft times the expectation was expressed that they would be sent to Russia. Stories of mail being lost in the Atlantic were also a cause for concern. The first mail from Australia arrived on the 9th of November. Jim's first letter from home came on the 14th, much to his relief and joy. This letter was forwarded from Williamtown on the 5th of August.

One of the first observations since arriving in England was the vast number of men and women in uniform seen on the streets in the cities and towns. Jim frequently heard civilians asking why a second front had not been opened in Western Europe.

Jim was fortunate to meet Cornish people at various functions and was always warmly greeted. He was made welcome at Masonic Lodge meetings and received many invitations to visit the homes of Lodge folk he met. Hospitality was also extended by some RAF colleagues who lived locally. He always enjoyed the home cooked meals and warm firesides.

On several occasions Jim accepted invitations to speak on his impressions of England and about Australian customs and life-styles. He spoke to school children about indigenous Australians and was impressed with the questions they asked. Once he was complemented by a local for picking up the English language so soon after arriving in the country.

The 13 Australians received notice that they were to leave Perranporth on the 28th of November, to rejoin 457 Squadron on the Isle of Man.

This sojourn on the Cornish north coast provided Jim in later life with many enduring warm memories of his time in England.

Ollie was discharged from RAAF on the 30/10/1945.